|

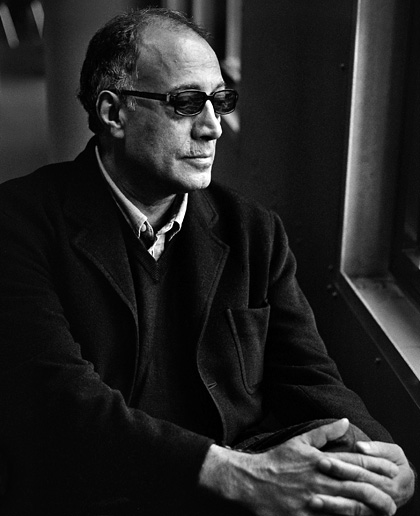

| Abbas Kiarostami |

Open case: Kiarostami's film reemerges after 30 years

by MEHRZAD BAKHTIAR (Tehran Bureau)

In the magnificent haste and enthusiasm of Iranians to share insight about the questionable presidential election in June, a number of significant cultural artifacts, either forgotten or previously unheard of, have been brought to light. One such gem is Abbas Kiarostami's Ghazieh Shekle Aval Shekle Dovom or First Case, Second Case.

Kiarostami is a canonized filmmaker both inside and outside of Iran, yet this highly important work managed to remain under the radar of even most cinema enthusiasts until just a few months ago when it appeared online. Free and widely available, it affords us the opportunity to examine Kiarostami's astute social observations through the lens of recent history.

The 47-minute documentary begins by depicting a scenario: a teacher drawing a diagram on the chalkboard with his back to the class is interrupted several times by the sound of a pen banging rhythmically against a desk. Each time he turns around, the noise stops, only to resume again. Finally, unable to pick out the culprit, the teacher tells the seven boys sitting in the corner of the room to leave the class. The students are given an ultimatum, which becomes the basis of the film: either (case one) they inform the teacher who was causing the disturbance, or (case two), they will all be suspended for a week. Kiarostami then goes on to interview the fathers of the students, as well as ministers, religious leaders, writers, filmmakers and directors of educational institutions about their opinions as to the proper course of action.

The initial appeal of the film lies in the presentation of this very dilemma. Rather than take a moral stance on the issue, Kiarostami depicts each case with a sense of removed neutrality. We are encouraged to weigh two deadlocked positions against each other; each has its advantages and disadvantages, and there is no nuanced third way out. Those viewers who are unable to reduce their vales into a cut-and-dry answer will likely agree with writer and filmmaker, Noureddin Zarrinkelk, that "a clear answer is really very difficult to come up with."

After this first response, the film cuts to a head-on shot of a working projector, invoking in the viewer the feeling that the film of the students in the class is being projected onto their person, that he or she is in fact one of the children faced with this moral decision.

As the film continues, however, we see that few of the interviewees are as torn or impartial as Zarrinkelk. Having been shot in 1979-80 and released in 1980, only a year after the Islamic revolution, most answers are impassioned and highly politicized. The question is not merely one of a student disrupting a class and a teacher doling out whatever punishment he deems fit. Whether or not the analogy is explicitly made, most of the people interviewed see the scenario as a greater issue of solidarity versus selling out, of standing one's ground against an abuse of power, versus giving into, and hence supporting that power.

In addition to still-popular celebrities like Iranian actor Ezzatolah Entezami and filmmaker Masoud Kimiai, First Case, Second Case includes a cast of important political figures: Ebrahim Yazdi, for example, was an active member of the National Resistance Movement as well as the Freedom Movement of Iran. He became Foreign Minister after the revolution, only to step down in less than a year in opposition to the hostage crisis. Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, then director of the Islamic Republic's Radio and Television Network, would replace Yazdi, only to be executed in less than a year for allegedly plotting to assassinate Khomeini. Other figures include Kamal Kharazi, who would become Minister of Foreign Affairs during the Khatami administration, and Ayatollah Sadegh Khalkhali, the notorious Revolutionary Court magistrate who sentenced a great number of former government officials to execution.

The obvious, retrospective irony, of course -- the element that makes this film even more compelling now than when it was made -- is the sight of so many important figures supporting a revolution that would come to embody a totalitarian government, itself completely intolerant of the very same rebellion and resistance they promote in their films.

Whether or not Kiarostami could foresee what this film would come to mean is ultimately irrelevant. Either way, he was able to put his finger on an issue that beautifully captured the fervent dynamics of a historical moment. What resulted was a film from which, thirty years later, every Iranian can still learn. (From Tehran Bureau)

No comments:

Post a Comment